|

I recently took part in the Australian National Health and Wellbeing Bushfire Survey, conducted by the Australian National University. The study waw looking into the long-term psycological effects of bushfire on communities and individuals. A great animation has been created to summarise the results, which you can view here: youtu.be/CT-Nlp_RWzc

This morning I came across a nice little story from Gardening Australia about landscape gardening in an extreme bushfire area, one of my favourite subjects. There is so much our gardens can offer for bushfire resilience and protection. Watch the story here: youtu.be/0g__iieMiUI

Some people ask me what the significance or relevance of permaculture to bushfire resilience, I am planning an essay (or maybe a book!) on this subject, but in the meantime I recommend watching this great youtube: https://youtu.be/y_HEHlE-_dE or read 'The Flywire House' by David Holmgren: https://store.holmgren.com.au/product/the-flywire-house-ebook/

I was recently interviewed by ABC Central Victoria about my house and how it relates to bushfire design and planning. It has been several years in the making, incorporating elements of pushfire planning and design at every stage of development. Check it out here:

www.abc.net.au/news/2022-08-10/eco-living-in-central-victoria-village-energy-efficient-houses/101318668?utm_campaign=abc_news_web&utm_content=link&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_source=abc_news_web Hamish MacCallum 16 January 2020

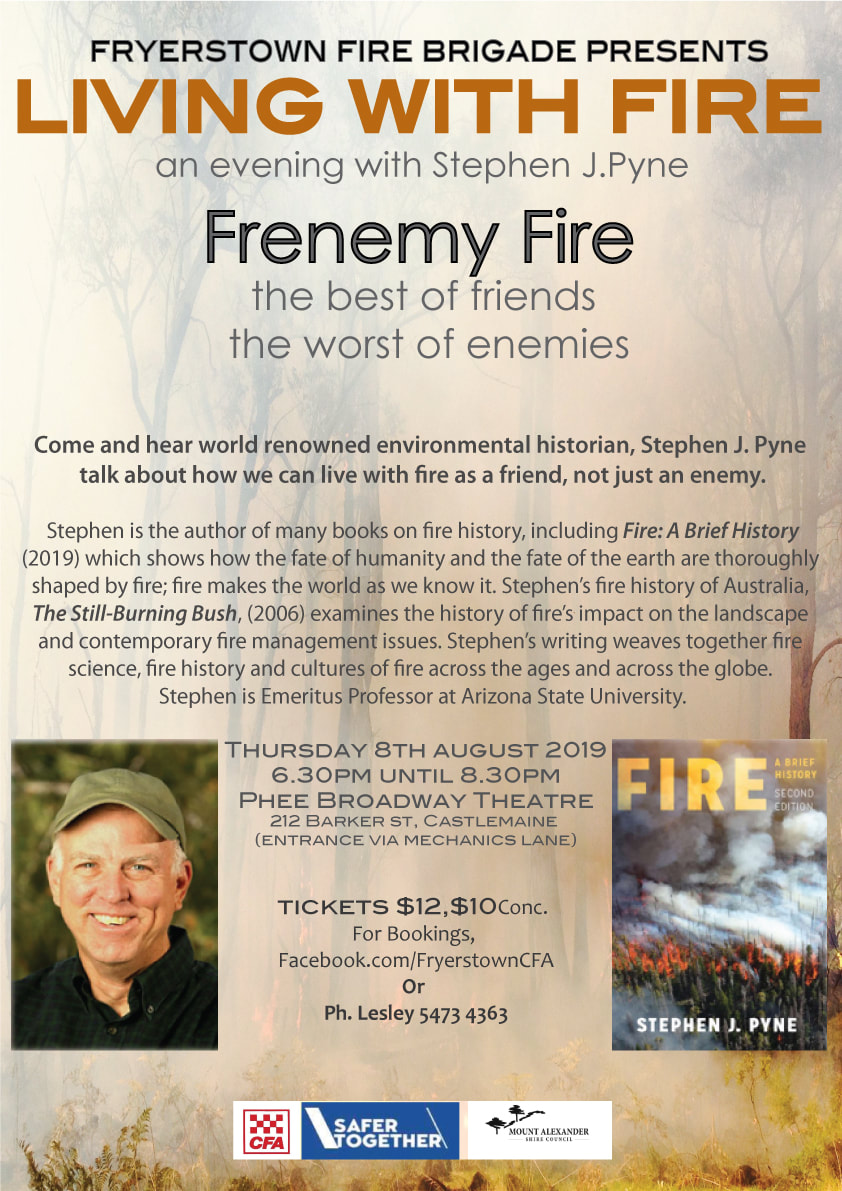

Fire. How do we respond? Bushfire Planning in a Hotter World “We survive fire by living with it. If at times it seems our worst enemy, it is also our best friend. We can’t thrive without it.” Stephen Pyne. I am writing this between long-haul deployments to the fires in East Gippsland, where I have been working as a volunteer firefighter with the CFA. Something that has been remarkable about this fire season is not the obvious size or severity of the fires but the scale of discussion on fuel and landscape management, so many people who had previously little interest in fire or landscape management suddenly seem to know exactly what should be done. The issue is clearly emotive, with opinions and convictions on the appropriate response. As a bushfire and land management consultant and I am often asked (at the moment sometimes several times a day) what we should be doing to better manage landscapes to avoid further catastrophe. The answer I give often fails to relieve the obvious tension people are feeling in their search for a solution to a battle we are obviously losing, “It depends”. Every landscape is of course different, along with the ownership and responsibilities that go with them, different inputs and outcomes dictate a multitude of different ways to deal with the issue. This may seem like a deflection from an obviously serious issue but techniques are only the toolbox to be wielded when we know what the underlying problem is. What is the problem? Like in medical diagnostics it is critical to look at the underlying issue rather her than the obvious condition, for instance it is more effective to stop smoking than treat lung disease. With fire fuel management we need to look less at removal of forest fuels (burning) and more closely at forest management itself. Research has shown that clear felling forests makes them more prone to causing severe fire, especially as they reach the 10 to 30 year stage. Crowded stems in forests lead to moisture stress and an accumulation of ladder fuels, leading to greater crown fire potential. Selective thinning techniques have been shown to rapidly increase tree height, making them less prone to crown fire. This also increases space between canopies and reduces moisture stress and therefore ladder fuels (stressed Eucalypts put out foliage all along their trunks and branches). The issue with losing properties to bushfire is compounded by removing the most valuable asset, people. By advocating leaving we only encourage further disconnection from the landscape and further alienation from our relationship with fire, turning friend into foe. This in turn increases further pressure on the environment through resource extraction to rebuild what was lost. The increased fire risk further drives people away from the rural landscape, leading to further disconnection and the loss of skills and bodies needed to embed appropriate cultural practices for fire management. That’s not saying we should all stay and defend, once again, “it depends”. Living in rural areas comes with the risk of fire. Importantly, how we manage our own land and infrastructures can directly affect our neighbours and communities. It is imperative that the cultural land management paradigm extend to the peri-urban environment, where most rural populations live. This relatively new cultural domain is where education, skills and training are needed to design and manage fire resilience in housing and landscape. The concept of community fireguard needs to be re- kindled and expanded to become a cultural obligation, the recent fires have shown how effective community based firefighting crews can be at protecting their communities. During my deployment in Mallacoota I saw the evidence of a community that pulled together every possible resource and able body to protect the town. Wheelie bins full of water and a mop stood out on the street, buckets lay by front yards. Blackened circles, evidence of a spot fire that failed to take hold, interrupted in its spread by an informal volunteer firefighter. Fighting fire with fire (and fungi) Traditional land management has been mitigating the problem of severe wildfire for thousands of years. The massive upheaval of indigenous people and landscape has had a huge effect on wildfire. In many parts of Australia we have lost the knowledge and skills of traditional burning techniques, along with a landscape more naturally resilient to wildfire spread. The land has changed so significantly that a whole new paradigm of fire management will need to be learned. However, again the techniques are less important than the principles guiding them. Something that struck me during the National Indigenous Fire Workshop (Dhungala, 2019) was the concept of the Eucalyptus forest litter smothering the ground, like a sickness. Fire was seen as a healthy remedy to this. The over-representation of eucalyptus in the forests is a compounding factor , cool fire was a preventative measure to keep open country from being overgrown. From an ecological perspective, less trees in our forests means less competition, leading to taller growth, more drought resilience and the forest being less prone to severe fire. Higher moisture levels in the landscape encourages decomposition of forest fuels, often overlooked as an effective tool for fuel reduction. Fungal decomposition of forest fuels leads to significant soil building, carbon and water storage. A well functioning forest ecosystem would effectively be digesting its own fire fuels. What we can learn from this is how to strategically encourage this process, with skills and techniques based from traditional knowledge and modern science. Ironically the environmental movement has been in part responsible for the misguided notion that more trees in forest systems means a healthier forest. The creation of the national park was a double edge sword, the separation and disconnection from the human/nature relationship is arguably perpetuated by forest protection and idolisation. Here in central Victoria evidence of pre-European landscapes tell a different story, anecdotes form early settlers described a “park like” landscape, open fields and large, widely spaced trees in a mosaic pattern, carefully managed with cool fire an strategic grazing to maintain the mosaic. Once again traditional knowledge can effectively inform an appropriate response. It may seem somewhat paradoxical that the new wave of greenies will wield chainsaws and drip torches (my neighbour coined the term ‘Greennecks’, a comment on our love of nature, chainsaws, and guns). The problem is the solution In permaculture the aphorism “the problem is the solution” guides our observations to become without judgement, allowing a broader perspective to be considered. In context, the removal of trees from the central Victorian forests may present its own problems, such as how can we reduce the impact of forestry on other species? How do we use the carbon removed from the forest? How can we have a positive effect on the forest while creating significant gains in fire management? How does the removal of trees from a forest lead to a healthier, fire resilient landscape? Although this is possible, once again the answer is “it depends”. Fryers Forest The intentional community based outside Fryerstown was originally developed using permaculture principles to guide the village construction and continuing land use. It is nestled into one of Victoria’s significantly fire-prone landscapes, making fire management a priority outcome in any decisions around land use. Lucky for us, we love chainsaws. Lucky for the forest, we love trees also. 25 years later, hundreds of trees chopped down and the result is significant. A trip through our front gate shows a striking difference between the state forests on one side and our management regimes on the other. The trees are significant larger, the forest floor capable of supporting herbaceous understory, parts are being opened up to native grasslands, a mosaic of land use is emerging. As with the permaculture aphorism, the problem of overcrowded forest has led to positive outcomes. Healthier forest, less fire risk, fuel for cooking, hot water and heating. Turning fire to our friend has reduced the risk of fire being our enemy. In future we hope to continue this relationship with the forest we love, using fire to generate electricity (biomass gasification), burning the land to encourage specific plant communities (cultural burns) and continue to promote bottom-up solutions with broader community engagement in the landscape we have chosen to live with. The following is an account of my deployment to  Hamish MacCallum 17 January 2020 Mallacoota fires Supporting a community in crisis In the first week of January 2020 I volunteered to join a strike team of 22 firefighters deploying to Mallacoota on Victoria’s east coast to relieve crews from our district who had been previously deployed Mallacoota, like many east coast communities was isolated from the rest of the country and the roads in would take weeks to clear. We were due to fly in on the 2nd but smoke was making it impossible to land aircraft safely. Thousands of people were stranded and no one was coming in or out. We finally hit the road on Saturday the 4th, still unsure how or when we would get to Mallacoota. It was another hot, windy day and we all had no idea what to expect. Like fire, the nature of long haul deployment is unpredictable. We expected that once we got in, we wouldn’t know how or when we would get out. Five hours on the bus and we began to see the fires consuming half of East Gippsland. A sense of silent foreboding permeated the bus. We were approaching a large, dark mass of sky, like a lurking behemoth waiting to swallow us. Information and instructions were dynamic, we were a small part of a massive logistical operation, unprecedented, as many have stated. We arrived at Swan Reach staging area, a large encampment of emergency service workers set up on the local sports oval. The sea of tents and hordes of firefighters, SES, ambos and all involved in looking after the well-being of hundreds of people became our community for the night. We ate food, rubbed shoulders with firefighters from the USA and all over Victoria and played cricket while we waited patiently for the go ahead. By early afternoon the following day we finally had word we would fly out of the ADF air training base at Sale which had rapidly become the centre for air operations supporting the rescue and relief efforts to the communities under siege. Evacuees were arriving on the aircraft now landing. This was to be our ride into the fire grounds. We waited for the Chinook to be fuelled and loaded with supplies before boarding. The atmosphere of teamwork and comradeship amongst the ADF, CFA, police and other relief workers/relief teams as we went on board was a great example of how Australians come together in crisis. The Chinook waited for us on the tarmac and we made our way on board. The flight path hugged the coast and soon enough we were seeing the burning landscape, held in check only by the rugged coast. As we landed we were enthusiastically greeted with cheers and applause from the next round of evacuees waiting on the tarmac for their way out of an arduous and challenging week in Mallacoota. Visible relief is an understatement. They had involuntarily been through hell and they had overwhelming admiration for those who choose to put themselves in their place. We were surrounded by a blackened landscape, and it was clear to us that people had worked hard to save the air strip and terminal. It was lucky for everyone that they’d managed it - or rather it was a combination of hard work and bravery. We were met at the airport by a CFA volunteer who gave us a briefing on what to expect. We were to be putting out smouldering fires and providing the community with information, logistical support, reassurance and counselling. The community was traumatised by an experience that can weaken the knees of even the toughest veteran firefighters. Listening to their stories was as important as any of the many tasks ahead. Over 100 houses and two lives had been lost in Mallacoota, amazingly much of the towns infrastructure had survived intact. After another briefing at the fire station we were allocated our accommodation for the night, an Air b’n’b, normally occupied by families now heading home by ship or plane from their interrupted summer holidays. We headed to the pub which was to be our hub for food and time out each morning and evening. CFA, police, ambos, MFB impact assessment teams and other emergency workers became the main patrons for a pub normally bustling with locals and holidaymakers. As we walked to pick up our tanker evidence of a hard fought battle against the ember storm became apparent. Spot fires had started all around, some quashed before taking hold, some taking out a row of trees or a garden fence before being extinguished, others unable to be quelled before consuming houses, sheds or anything the developing fire could grasp. This was obviously a hard fought battle and the whole community had been involved. Evidence of the weapons from the fight lay around the town; buckets in driveways, wheelie bins filled with water and a mop on the nature strip on the main drag. We made our way to our accommodation, squeezed 16 tired firefighters into beds (some of us doubling up for the night) in a lovely house with a stunning view; no electricity a reminder that we were still on an active fireground. The next morning we breakfasted at the pub again before being briefed at the fire station. We were allocated a sector to manage and tasked with blacking out, identifying dangerous trees (there were many still burning) for the specialist tree fellers to drop. This job in itself will need to be done for weeks, if not longer. Patrolling and talking with he locals quickly became an important role to keep up the spirits of the local community, who are in my opinion the true heroes of Mallacoota. We were warmly greeted everywhere we went. It was clear that just our being there was an enormous boost to the locals. We stopped by a house near the edge to a forest with still burning trees and was greeted by a woman who shared her story. Anger and frustration were expressions of the trauma she had experienced; she gave us all a hug and shed a few tears. Next door we helped an old man with his shopping while he shared his account of the fire. He had a lucky escape, others were not so fortunate. Around the corner a burned out house was cordoned with crime scene tape, we knew not to go there. In our sector there was a large gully complex that remained untouched by fire. The sounds of the environmental refugees filled our senses - the calls of birds sharing unfamiliar territory. It was clear this was an important oasis that needed protection from the smouldering fires surrounding it. We were working in unfamiliar territory. I had an awesome crew with me; we bonded well through clear communication, collective problem solving and humour. We stuck together and kept each other safe, having moments to relax and reflect, keeping up our morale in unique circumstances. On our last day of the rotation the road was finally cleared to Gypsy Point, a small community that had been isolated by the fires. As we drove through the burnt forest it told the story of its direction of travel, varying intensity and level of destruction. In some parts the fire would have been terrifying. We arrived at Gypsy Point and were tasked with cleaning up the roadside from trees that had fallen or had been felled. Obviously dangerous trees are quickly identified and removed. Time will reveal many more weakened by the fire, as their supporting roots smoulder away beneath the hot, dry soil. These roads will remain unsafe for some time. At the end of our deployment the smoke was playing havoc with air support once again, so our journey home was to be on the HMAS Choules, the ship that had evacuated so many stranded families from the Mallacoota foreshore. I had family friends who had been on the first evacuation, with over a thousand others. We joined the last group of 200 evacuees along with 44 dogs, and police and other emergency workers rotating their shifts. The crew of the Choules were awesome - we were made to feel at home and invited to explore the ship, from the enormous docking bay to the bridge. We were told if a door was unlocked, to feel free to go in. Such extraordinary kindness and generosity kept us all in high spirits and proud to be a part of the huge community supporting the people and animals whose lives will be forever marked by this bushfire season. For me a positive that has come from the fires is being reminded that care and generosity are traits we all share and that most of us give freely without question. Over the months ahead many emotions will be expressed by the people who were caught in that terrible situation; outrage, anger, sadness, frustration. These will fade in time. For me the sense of joy in working together with so many souls to help others is the enduring foundation of being a firefighter. I offer huge thanks to the team who joined me on this deployment, in particular my own crew; your skills, experience, kindness, consideration and commitment were exemplary. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-08-10/eco-living-in-central-victoria-village-energy-efficient-houses/101318668?utm_campaign=abc_news_web&utm_content=link&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_source=abc_news_web Fire. How do we respond? Hamish MacCallum 16 January 2020 Fire. How do we respond? Bushfire Planning in a Hotter World “We survive fire by living with it. If at times it seems our worst enemy, it is also our best friend. We can’t thrive without it.” Stephen Pyne. I am writing this between long-haul deployments to the fires in East Gippsland, where I have been working as a volunteer firefighter with the CFA. Something that has been remarkable about this fire season is not the obvious size or severity of the fires but the scale of discussion on fuel and landscape management, so many people who had previously little interest in fire or landscape management suddenly seem to know exactly what should be done. The issue is clearly emotive, with opinions and convictions on the appropriate response. As a bushfire and land management consultant and I am often asked (at the moment sometimes several times a day) what we should be doing to better manage landscapes to avoid further catastrophe. The answer I give often fails to relieve the obvious tension people are feeling in their search for a solution to a battle we are obviously losing, “It depends”. Every landscape is of course different, along with the ownership and responsibilities that go with them, different inputs and outcomes dictate a multitude of different ways to deal with the issue. This may seem like a deflection from an obviously serious issue but techniques are only the toolbox to be wielded when we know what the underlying problem is. What is the problem? Like in medical diagnostics it is critical to look at the underlying issue rather her than the obvious condition, for instance it is more effective to stop smoking than treat lung disease. With fire fuel management we need to look less at removal of forest fuels (burning) and more closely at forest management itself. Research has shown that clear felling forests makes them more prone to causing severe fire, especially as they reach the 10 to 30 year stage. Crowded stems in forests lead to moisture stress and an accumulation of ladder fuels, leading to greater crown fire potential. Selective thinning techniques have been shown to rapidly increase tree height, making them less prone to crown fire. This also increases space between canopies and reduces moisture stress and therefore ladder fuels (stressed Eucalypts put out foliage all along their trunks and branches). The issue with losing properties to bushfire is compounded by removing the most valuable asset, people. By advocating leaving we only encourage further disconnection from the landscape and further alienation from our relationship with fire, turning friend into foe. This in turn increases further pressure on the environment through resource extraction to rebuild what was lost. The increased fire risk further drives people away from the rural landscape, leading to further disconnection and the loss of skills and bodies needed to embed appropriate cultural practices for fire management. That’s not saying we should all stay and defend, once again, “it depends”. Living in rural areas comes with the risk of fire. Importantly, how we manage our own land and infrastructures can directly affect our neighbours and communities. It is imperative that the cultural land management paradigm extend to the peri-urban environment, where most rural populations live. This relatively new cultural domain is where education, skills and training are needed to design and manage fire resilience in housing and landscape. The concept of community fireguard needs to be re- kindled and expanded to become a cultural obligation, the recent fires have shown how effective community based firefighting crews can be at protecting their communities. During my deployment in Mallacoota I saw the evidence of a community that pulled together every possible resource and able body to protect the town. Wheelie bins full of water and a mop stood out on the street, buckets lay by front yards. Blackened circles, evidence of a spot fire that failed to take hold, interrupted in its spread by an informal volunteer firefighter. Fighting fire with fire (and fungi) Traditional land management has been mitigating the problem of severe wildfire for thousands of years. The massive upheaval of indigenous people and landscape has had a huge effect on wildfire. In many parts of Australia we have lost the knowledge and skills of traditional burning techniques, along with a landscape more naturally resilient to wildfire spread. The land has changed so significantly that a whole new paradigm of fire management will need to be learned. However, again the techniques are less important than the principles guiding them. Something that struck me during the National Indigenous Fire Workshop (Dhungala, 2019) was the concept of the Eucalyptus forest litter smothering the ground, like a sickness. Fire was seen as a healthy remedy to this. The over-representation of eucalyptus in the forests is a compounding factor , cool fire was a preventative measure to keep open country from being overgrown. From an ecological perspective, less trees in our forests means less competition, leading to taller growth, more drought resilience and the forest being less prone to severe fire. Higher moisture levels in the landscape encourages decomposition of forest fuels, often overlooked as an effective tool for fuel reduction. Fungal decomposition of forest fuels leads to significant soil building, carbon and water storage. A well functioning forest ecosystem would effectively be digesting its own fire fuels. What we can learn from this is how to strategically encourage this process, with skills and techniques based from traditional knowledge and modern science. Ironically the environmental movement has been in part responsible for the misguided notion that more trees in forest systems means a healthier forest. The creation of the national park was a double edge sword, the separation and disconnection from the human/nature relationship is arguably perpetuated by forest protection and idolisation. Here in central Victoria evidence of pre-European landscapes tell a different story, anecdotes form early settlers described a “park like” landscape, open fields and large, widely spaced trees in a mosaic pattern, carefully managed with cool fire an strategic grazing to maintain the mosaic. Once again traditional knowledge can effectively inform an appropriate response. It may seem somewhat paradoxical that the new wave of greenies will wield chainsaws and drip torches (my neighbour coined the term ‘Greennecks’, a comment on our love of nature, chainsaws, and guns). The problem is the solution In permaculture the aphorism “the problem is the solution” guides our observations to become without judgement, allowing a broader perspective to be considered. In context, the removal of trees from the central Victorian forests may present its own problems, such as how can we reduce the impact of forestry on other species? How do we use the carbon removed from the forest? How can we have a positive effect on the forest while creating significant gains in fire management? How does the removal of trees from a forest lead to a healthier, fire resilient landscape? Although this is possible, once again the answer is “it depends”. Fryers Forest The intentional community based outside Fryerstown was originally developed using permaculture principles to guide the village construction and continuing land use. It is nestled into one of Victoria’s significantly fire-prone landscapes, making fire management a priority outcome in any decisions around land use. Lucky for us, we love chainsaws. Lucky for the forest, we love trees also. 25 years later, hundreds of trees chopped down and the result is significant. A trip through our front gate shows a striking difference between the state forests on one side and our management regimes on the other. The trees are significant larger, the forest floor capable of supporting herbaceous understory, parts are being opened up to native grasslands, a mosaic of land use is emerging. As with the permaculture aphorism, the problem of overcrowded forest has led to positive outcomes. Healthier forest, less fire risk, fuel for cooking, hot water and heating. Turning fire to our friend has reduced the risk of fire being our enemy. In future we hope to continue this relationship with the forest we love, using fire to generate electricity (biomass gasification), burning the land to encourage specific plant communities (cultural burns) and continue to promote bottom-up solutions with broader community engagement in the landscape we have chosen to live with. https://www.science.org.au/curious/earth-environment/how-survive-bushfire

|

AuthorHamish is a wildfire management consultant and permaculture designer, volunteer firefighter and father of three wildlings Archives

May 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed